The Pertinence of Park Mews

I was sitting in my office one day minding my own business when the phone rang.

The caller introduced himself as comedian Billy Connolly’s New Zealand agent.

“Billy wants to meet you,” he said.

Apparently on the way in from the airport, he’d passed Park Mews in Hataitai and stated: “The architect clearly possesses a sense of humour.”

As such, I got to appear on his World Tour of New Zealand and subsequently had backstage invitations every time he has appeared in Wellington.

He then invited me to inspect a site, he and wife Pamela were considering for a new build in Great Mackerel Bay, an hours ferry ride across Pittwater from Palm Cove, in Sydney.

Sadly for me, before they could commit to the stunning site, Billy was offered a plum TV role in a US sitcom, and their plans changed.

While Billy might be the most famous fan of Park Mews, he is not alone in noticing it en route from the airport.

A while back I was a passenger in a taxi also carrying an American tourist.

“My god”, he exclaimed. “Is that for real or is it a put on?” Taxi drivers are well known for the originality of their thinking, so this one’s response was a classic. Straight faced the driver answered. “That was built during the time of a Labour Government when it was required that everyone had their own roof over their heads.”

Jokes aside, I’m really stoked that Park Mews has this week been honoured with an enduring architecture award from the Wellington Branch of the New Zealand Institute of Architects.

While there are some things about it that would not get a current tick of approval from the council, the design of town housing that encompasses both a sense of community and privacy while being close to public amenities is something that is still dear to my heart. It is an essential way of combatting suburban sprawl.

Park Mews was commissioned by an adventurous property developer, Campbell Homes. It was completed in 1974 with 32 unit titled apartments of various configurations on several levels. Private outdoor gardens or private roof decks are attached to each apartment.

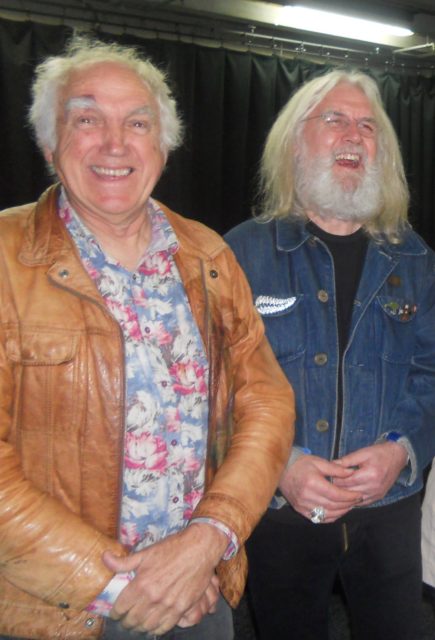

I had been somewhat inspired by pictures I had seen of Saftie’s Habitat 67 – a Montreal design that I still found inspirational when I visited it for a first time a couple of years ago. (The pic is of me a couple of years ago, not 45 years ago!)

I had been somewhat inspired by pictures I had seen of Saftie’s Habitat 67 – a Montreal design that I still found inspirational when I visited it for a first time a couple of years ago. (The pic is of me a couple of years ago, not 45 years ago!)

Our architectural concept in the early 1970s was to marry the sterile repetition of apartment blocks with the random ‘looseness’ of suburbia, in other words to blend these two typologies into a fragmented expression of individuality with good natural light, privacy and community on a relatively small footprint of land. The building is mainly a white painted assembly of individual dwelling forms, offset with brightly coloured pipe windows which act as abstracted flowers calling up the garden setting of detached houses.

Constructionally it’s possibly the most complicated reinforced blockwork building ever built in NZ and its interlocking cellular design has resisted seismic events during its 45 year life.

The structural engineer that took it on had worked overseas for many years for the Arup Group who, among other projects, engineered the Sydney Opera House.

To their credit, the Wellington City Council issued a Building Consent, which is something that would be very difficult now, with the dumbing down of planning rules, and the inexplicable push by some urban designers to homogenise our built environment.

But the building has not been without legal difficulties. Shortly after its completion the neighbour to the north sued Campbell Homes for loss of his privacy because he was being overlooked by a mass of new townhouses.

In response Campbell Homes countersued that the neighbour’s somewhat dilapidated dwelling, was devaluing his new townhouses.

The judges decision was ‘that because these neighbours clearly can’t stand the sight of each other’s buildings, a 10m high wall should be built on their common boundary and that the parties should share the costs equally. After the legal bills were paid there was nothing left to build the wall!

The sense of community that Park Mews inspired was perhaps best illustrated when the then Minister of Housing asked me if he could pay a visit with me to the new development. It was a Friday night. We knocked on four or five doors with no response.’ They are all out’ said the Minister. We tried one more door to behold a mass of people inside. ‘We take turns at hosting our community gatherings so that we can look at fellow resident’s apartments,’ they said.

The Minister was impressed, but just like with Billy Connolly, we never got a commission.